Book List: The Dictator and The Picture Book

- Raymond Huber

- May 25, 2017

- 6 min read

Children's author, writing teacher and editor Raymond Huber is fascinated by the way in which children's writers have used picture books historically to fight dictators. This is especially apt right now (ahem), so here are a few books he would recommend.

The final page of The Story of Ferdinand (1936) shows Ferdinand after he has returned from the bullrings of Madrid. He sits peacefully on his hill.

Image source: A Subversive Bull: Robert Lawson and the Story of Ferdinand.

A despot doesn’t fear eloquent writers preaching freedom – he fears a drunken poet who may crack a joke that will take hold. – E.B. White (One Man’s Meat, 1939)

E.B. White was writing at a time when dictators (Hitler, Stalin, Mussolini) were flourishing, unrestrained – and today there’s still no shortage of divisive world leaders. Picture books which challenge dictators and authoritarian regimes are a bit of a rarity – they tend to be ‘sophisticated’ books with themes more suitable for older readers. They expose children to issues of war and peace, authority and democracy, most often using humour to engage them.

It was great to see a title for younger readers published by Gecko Press recently. Don’t Cross The Line! by Isabel Minhó Martins (2016) is a picture book with a political message which also entertains mightily.

A dictatorial general orders a guard to restrict entry to the right-hand pages of the book but a crowd gathers on the border, wanting to use the space. Non-violent people power beats militarism in the end and the dictator reacts like a querulous child who wanted to be the star of the story.

This is an artfully designed book with sixty characters and eight daringly blank pages. The empty space speaks to all ages about freedom and oppression: children want to play in it; teenagers ask why it’s forbidden; and adults see the injustice of it. The edgy but fun illustrations by Bernardo Carvalho are a fine match for this timely tale.

As White said, humour can be a more potent force than eloquence, and these sophisticated picture books often use satire and mockery as their chief weapons. Adolf Hitler and the Nazis have justly been a major target. A witty attack on the Nazis came from an English picture book, Struwwelhitler (1941) by Robert and Philip Spence; itself a parody of the iconic Struwwelpeter (1845).

Published in aid of the War Relief Fund – supplying games and woollen comforts to our Fighting Services – Struwwelhitler mocks the Nazis with cautionary rhymes about Hitler and his henchmen, who by then already much blood on their hands:

See! the horrid blood drops drip

From each dirty finger tip;

Pie-crust never could be brittler

Than the word of Adolf Hitler.

Sometimes a gentle approach to humour is as effective as sharp satire. The Story of Ferdinand by Munro Leaf (1936) is a highly influential children’s book because of its archetype of the fighter who won’t fight.

The parable of a bull who likes to smell flowers instead of the combat in the arena was regarded as an insidious pacifist tract during the Spanish Civil War. The book was targeted by the dictators of the time: Ferdinand was banned by General Franco in Spain; it was burned by the Nazis; and Stalin responded (more creatively it might be said) by naming a gun after it.

Ferdinand’s personality was ahead of his time: he’s is a free-thinker who chooses a peaceful lifestyle instead of following the crowd. Eighty years old, Ferdinand has never gone out of print.

Dr Seuss (Theodore Geisel) took aim at Hitler during the war with 400 political cartoons, but his greatest satire on dictators was Yertle The Turtle (1958).

Yertle forces the ‘common’ turtles to form a tower beneath him so he can rule over more territory – much like Hitler, and in the draft version Seuss even drew Yertle with a moustache. The turtles suffer badly until one asserts their rights and resists with a tiny ‘burp’ which topples the tyrant into the mud. Seuss shows how dictators can fall when individuals stand up against them.

Comics were banned in France during the Nazi occupation, but Edmond-François Calvo (mentor of Asterix’s creator, Uderzo) was secretly illustrating a picture book that quickly became iconic after the Germans retreated in 1944.

The Beast is Dead! (La Bête Est Morte!) is a parody of Disney comic-books, using animal characters to represent wartime foes: the French as rabbits; the British as bulldogs; Mussolini, a hyena, German soldiers as wolves and Hitler as the biggest, baddest wolf: My dear little children, never forget this: these Wolves who perpetrated these horrors were ordinary Wolves.

Not all comics are slapstick: the Tintin picture books are intricate adventures. Tintin’s creator, Hergé (Georges Rémi) was a painstaking researcher, basing his illustrations on real settings and his plots on news events. King Ottokar’s Sceptre (1939) was published as the Nazis began their European take-over and it’s the most political of the Tintin stories.

Tintin fights to save a fictional country (Syldavia) from a neighbouring regime, at the same time as Germany took over Austria, Czechoslovakia and Poland. The treacherous General’s name is Musstler (Mussolini plus Hitler) and the invading army uses German weapons and tactics.

Hergé was anti-fascist and Nazi censors banned some Tintin books, but he was accused of being a sympathiser because he worked at a German-controlled newspaper.

Satire can be subtle or clever, but sometimes it’s just plain mocking. The picture book that most blatantly ridicules dictators is The Tin-Pot Foreign General And The Old Iron Woman by Raymond Briggs (1984), aimed at the leaders who initiated the Falklands War.

It contrasts realistic black and white sketches of soldiers being maimed with scenes of the luridly-coloured dictators – sexualised, metallic giants, not named, but clearly Margaret Thatcher and General Galtieri – fighting over a ‘sad little island’. This book is more suitable for teenagers, and is most definitely not intended for younger children.

The classic War and Peas by Michael Foreman (1974) is a gentler parable which pokes fun at military rulers using rich visual humour. The pictures appeal to younger children and the message reaches older readers; a tricky balance to achieve.

It’s the tale of two countries, one hit by famine and other living in luxury. The gross inequality that fuels warfare is shown by the metaphor of a landscape made of decadent cream cakes. The rich country invades the poor (a familiar pattern in our times) but is beaten back by a reaction of Nature in a happy ending.

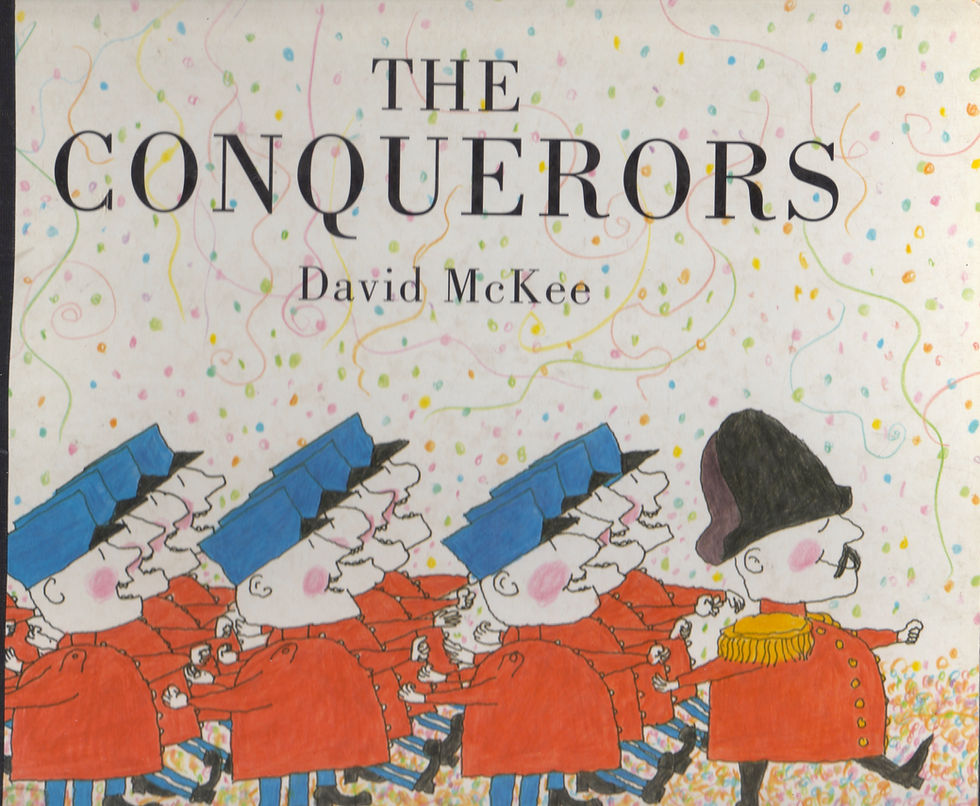

The most benign of all these picture books (and the one best suited to a young readership) is The Conquerors by David McKee (2004).

Yet another egocentric ruler of a large country aims to conquer every other nation by force, until one tiny country offers no active resistance. Instead, their peace-loving nature gradually ‘infects’ the soldiers and even softens the dictator himself.

There’s a bit of a mismatch here between the preschool characters and a complex social idea, but the basic storyline will appeal to children. Dictators are also found in the workplace, at school or at home.

Bravo! by Philip Waechter (2011, Gecko Press) is a junior picture book that imagines the response of a child to a dictatorial parent.

Young Helena’s life is fine except for one thing: her father is an angry man and he pushes Helena away with his frightening tantrums. When she’s had enough of this toxic climate, she takes control and leaves home. Illustrator Moni Port uses changes in colour, font and space to reflect the changing feelings of the tale.

The ending shows the importance of parental praise, and I think the story suggests that children also need to find peace within themselves.

These dictator-challenging books are fascinating politically and socially, they convey positive values, and they are great stories.

War books for young readers outnumber those which actively promote peace; one reason I wrote Peace Warriors (Mākaro Press, 2016).

While the parodies, Struwwelhitler and The Beast Is Dead!, are now historical artefacts, the other titles have not dated – and the oldest books, Ferdinand and Tintin, are more popular than ever.

raymond huber

Raymond is a children's author, freelance editor and writing teacher. His children's novels are Sting and Wings; his picture book, Flight of the Honey Bee, has been an international success. Raymond's non-fiction book, Peace Warriors, has inspiring stories of non-violent resistance (Mākaro Press). He's also written many school readers (Learning Media, McGraw Hill)) and textbooks for NZ and the US; short stories; and poems.

Comments